Beekeepers are often interested in improving the foraging opportunities near their hives, and one excellent way to do that is to plant flowering trees and shrubs. Of course, this isn’t the fastest way — but that is balanced by the ease of getting it done and the many decades of benefit for bees and other pollinators. Explore this guide to planting trees for bees to learn how to choose the best varieties for your location, and find tips and tricks for caring for newly planted trees.

Benefits of planting trees for bees

Trees offer a significant benefit: compared to ground-level plants, when they are in bloom, trees generally offer a highly concentrated number of flowers in a small area, increasing the bees’ foraging efficiency. When planted near a bee yard, trees also offer extra navigational assistance to returning foragers compared to a flat lawn or fields, helping the bees bring their hard-won cargo safely back home to their own hive. Tree planting requires the disruption of a relatively small footprint among the existing plants and once well-established, trees will do the heavy lifting to maintain their own dominance on the site.

Planning your bee-friendly planting

Begin by researching and choosing the best trees and shrubs for your location, including any special instructions for planting and protecting the trees until they can withstand ground-level menaces. Beekeepers can use trees’ concentrated flowering to good effect by choosing trees that bloom during the local periods of naturally low nectar and pollen production. In other words, rely on the existing plant mix for the traditional flows, but plant additional species, either for extra-early, or late-flowering periods or during any mid-season slowdown.

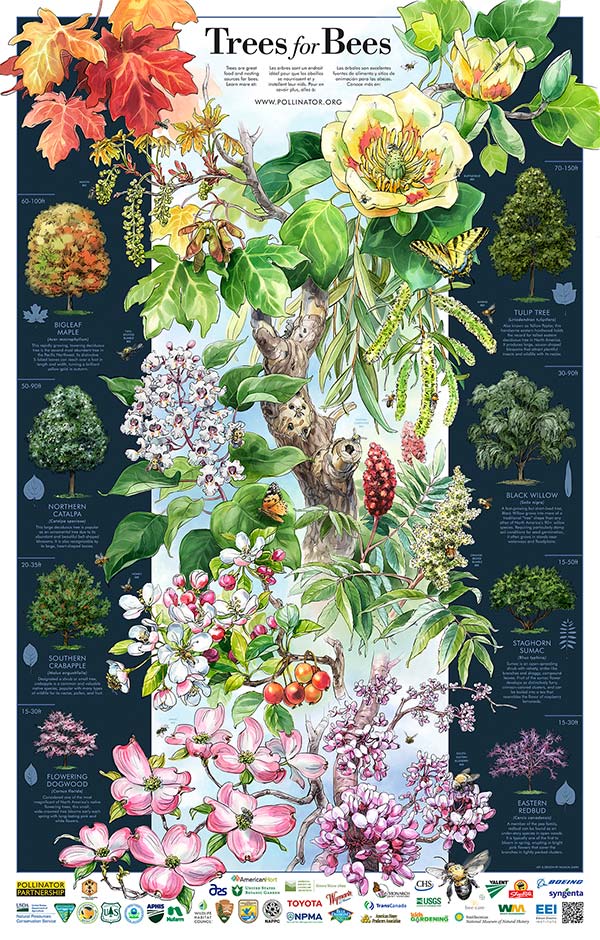

To determine which trees and shrubs are best for your location, look to local planting guides, books, and experts. We’ve rounded up some of our top recommendations, but this is by no means an exhaustive list.

Tree-planting information and resources

Before you plant, do the necessary research to find the best trees for honey bees — and your site. First, gather information about where you’ll be planting. The essential first step is to research your climate zone and the soil — two things that you cannot change.

- Find your horticultural zone. These zones are based on minimum winter temperatures and it’s best not to try to “cheat” (at least, not by much!) by choosing plants from much warmer areas than your own. While the trees might survive, they may not flower in colder areas. And, of course, flowering is the whole point of this project.

- Consider your site soil. Explore the Web Soil Survey (produced by the Soil Survey Staff, Natural Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture) for soil quality assessment and land use planning.

- Reach out to local experts. Your local Cooperative Extension or Soil Conservation Service can also help you tease out the basic soil information you need for choosing trees.

The best trees for bees

With the details about your site worked out, you can move on to thinking about what to plant. Not all trees are equally valuable to honey bees, so it’s important to choose carefully. While there are plenty of research options available, consider the resources listed below as a good starting point.

- The Pollinator Partnership is an organization that offers a very useful (and free) regional planting guide for pollinators, including bees.

- Two older, but still valuable, books about honey plants are both available online in .pdf format: Frank C. Pellet’s American Honey Plants (1920) and John H. Lovell’s Honey Plants of North America (1926).

- Peter Lindtner’s Garden Plants for Honey Bees offers reliable information about plants for bees.

- The Hive and the Honey Bee (Joe Graham, Ed.) is an encyclopedic book filled with reference material for beekeepers of all experience levels.

- For an excellent book on the best bee plants for the mid-central part of the US, explore Plants Honey Bees Use in the Ohio and Tennessee Valleys by Shannon Trimboli.

With so many trees and shrubs to consider, often the hardest job is winnowing down the list of possible choices. Explore the USDA plant database for more information about the range, and eventual size of any tree that catches your attention.

Consider bloom periods for consistent nectar flow

Next, think about at which point during the season you want to add nectar or pollen. Do you want early pollen to stimulate brood, late-season nectar to replace harvested honey, or a steady maintenance flow during a summer dearth? Use the blooming period dates to determine when the tree will be productive. There’s a tree for every use and every season.

There will likely be too many enticing options, so it’s a good idea to think of tree planting as a long-term project and plant a few every year to spread out the work. This will make it less of a chore and easier to fit into a busy life.

Don’t overlook tree size and space needs

With notes about the eventual size of your chosen trees, look at the intended planting site and determine whether the fully grown trees will fit. Use a tape measure to mark off on the ground the diameter of its expected spread. Now, look up: will the fully grown tree be near power lines, too close to a building, or block an important view? It’s a shame to spend the money and time growing a tree that will only be crudely hacked off when it outgrows its space. The time to work that out is before you plant, by moving the location, or going back and selecting a different, smaller tree variety.

Keep in mind, too, that the root area the tree may occupy will be as large as the branches overhead. Don’t let it imperil your septic tank or grow buried utilities or make cracks in your patio. If you need to know about buried gas, electric, or water lines call 811 for the free underground utility locating service.

Where to purchase trees for planting

While many nurseries sell trees, remember that the trees and shrubs you have decided to plant may require a special order. An excellent mailorder source of woody plants that provide a food source for honey bees is the Rock Bridge Nursery in Tennessee. Explore the options from Oikos Tree Crops Nursery or Cold Stream Farm Nursery — though not strictly bee-tree specialists, these nurseries carry some of the more unusual trees for honey bees.

In addition, many state tree nurseries offer tree and shrub seedlings that may be useful for bees, though often only in bundles of 10 to 50 very young trees of the same species. The best way to find these tree or shrub seedlings from your state forest nursery is to search your state name plus "state forest seedlings." You can also the NWF Trees for Wildlife program for planting tips, species recommendations, and fun activities for all ages.

How to plant trees and shrubs

For the best outcome, ask your supplier to send you planting instructions for your trees. Always follow their instructions, but consider these general recommendations for how to plant trees for the best results.

- Plant your trees as soon as they arrive, even in cold or rainy weather. While this may be unpleasant for you, it is very comfortable for the tree.

- The axiom in the nursery trade is that you don’t want to put a $10 tree in a $5 dollar hole, so take the trouble to make the planting hole large enough and backfill it exactly as described by the nursery.

- Even if it’s pouring rain, water the tree anyway to help get it off to the best start.

- After the tree is in the ground, lay down a 3-foot wide circle of weed barrier cloth and cover it with mulch.

- Growing trees need support: add a sturdy stake to help.

- Add a wire cage to surround the trunk (at least 8” in diameter, from ½” mesh hardware cloth, and at least two feet taller than the tree). While not attractive, cages are essential to protect small, vulnerable trees from lawn mower blades, critters, and deer.

How to care for newly planted trees

During the first year, you should plan on watering the tree every week. In the second year, you may only have to water during especially dry periods. And after that, if you have chosen carefully for your climate and soil, no watering will be necessary.

Check every year to make sure that neither the weed barrier cloth on the ground nor the wire cage are touching the trunk of the tree and restricting its growth. In a few years, after the tree has grown, you may need to replace the wire cage with a larger, taller one. Once the small brances are beyond the reach of browsing deer, you can remove the cage; by then, the bark is also likely to be unappealing to mice.

It may take a few years, or even longer, for your trees to start to feed your bees. Nothing compares to the satisfaction of seeing trees that you planted as saplings become tall, permanent parts of the landscape. If you have selected well, the trees may outlive you and be a gift to honey bees and pollinators long afterward. That’s a wonderful legacy to leave.

For more resources on planting for bees, explore our Beekeeper’s Guide.