As we noted last month, we have one hive that we’ve dubbed the “Scale Hive” located just outside the Betterbee office. It’s equipped with a Citizen Science Kit from BroodMinder. The data collected so far can be seen on our website here, which is updated every 5 hours.

It’s only had the BroodMinder equipment installed since early November, so we’re still feeling our way in interpreting the collected data. (And it’s just one hive, so our sample size is very small.)

But some interesting things are already apparent.

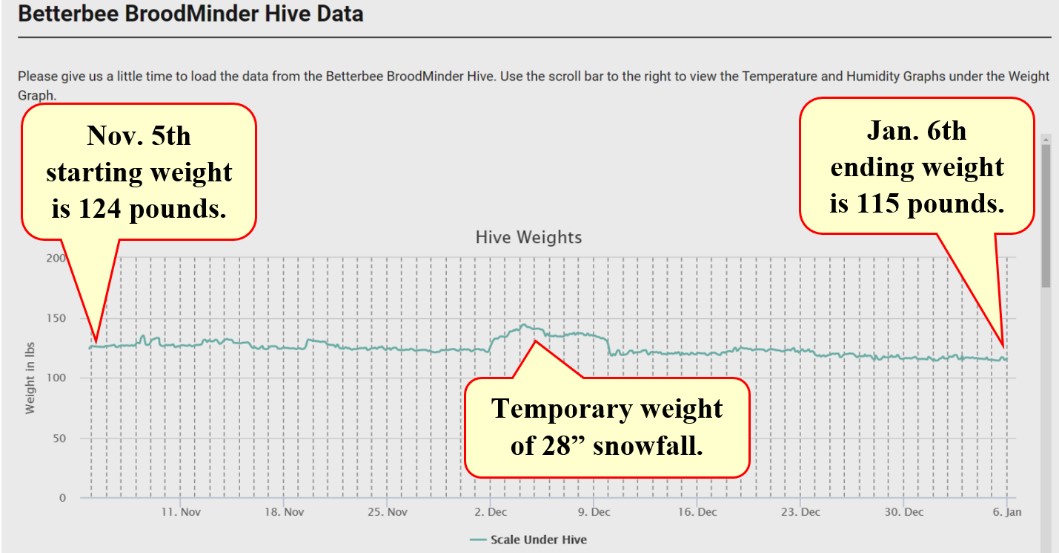

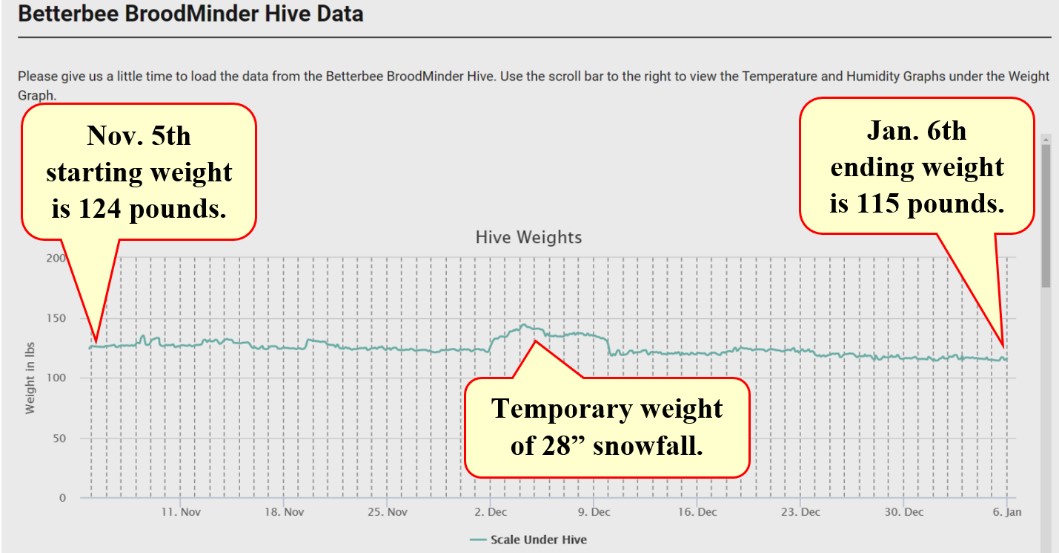

One of the biggest worries for beekeepers is whether their bees will run out of honey before they can forage again. From the date of installation (Nov. 4th) until the end of the year, the hive lost approximately 10 pounds of total weight. Since the weather and hive strength likely precluded any robbing, this can be assumed to be the weight of honey that the bees consumed. Ten pounds is slightly more than a full deep frame of honey. A 10-frame, double-deep, hive would likely have at least 12 full frames of honey, as well as some mixed frames that have both honey and stored pollen (bee bread) among the remaining 8 frames.

Over this nearly two-month period, it appears that the bees have eaten only 10%, or less, of their stores. Around here bees become self-sufficient again, just from foraging, by the end of April. With only twice the initial time period still to come, we should expect to have a lot of left-over honey still in the frames when winter is over, right? Not quite!

What’s missing here is the fact that at this time of year, the colony population is still shrinking from natural, seasonal, attrition so there are many fewer mouths to feed than later in the winter. But the most important thing is that the hive is not yet likely to have started raising brood in earnest. When that begins, the nurse bees must step up their own honey consumption in order to manufacture brood food to feed the larvae. And the colony as a group will have to consume much more honey in order to raise the cluster’s temperatures high enough to keep the brood warm enough to survive.That requires a temperature of 92 degrees F in the entire brood nest area. Broodless bees normally only need a minimum of the mid- to high-70 degrees F at the center of their cluster. The extra calories needed to keep the brood warm enough come from the adult bees consuming a very dense carbohydrate fuel: honey. So, while the first two months of non-foraging weather only used up a small portion of the colony’s stores, the two remaining two-month intervals will be much more “expensive” for the bees. That’s why beekeepers should continue to keep an eye on the total hive weight of the colony from now until dandelions bloom again.

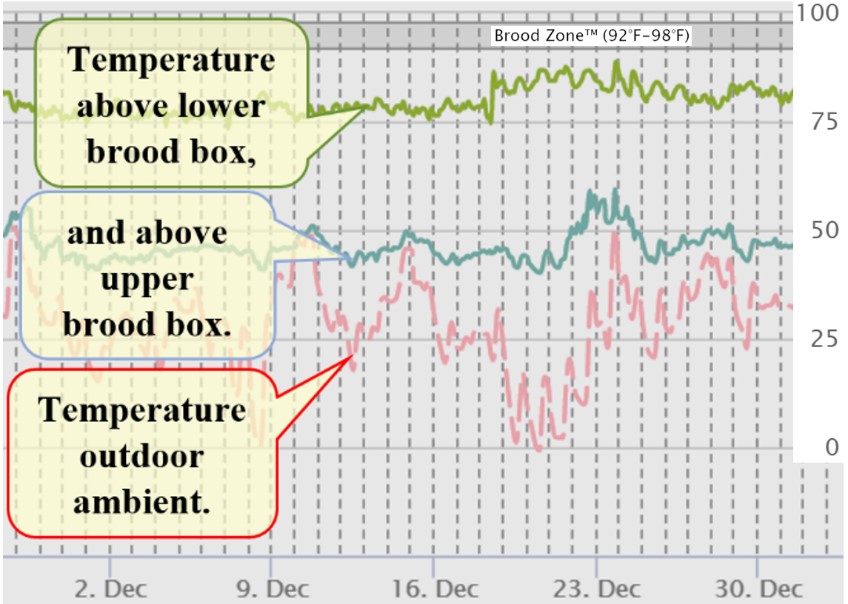

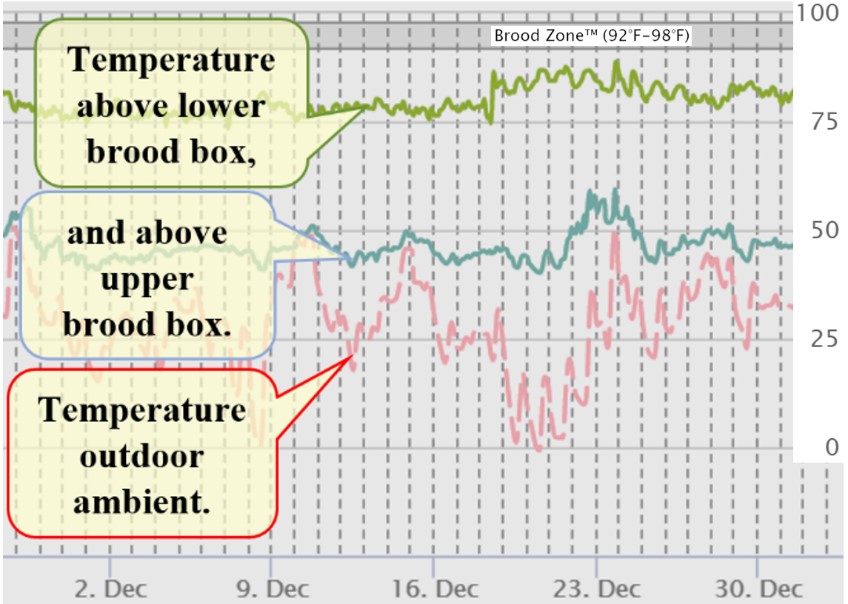

The second interesting thing to appear on the graphs was a sharp and sustained rise in the temperatures recorded at the top of the bottom box. The temps had been running in the mid- to high- 70s, but on the 18th of December, they jumped directly to the low 80s. The outside temperature during this period was dropping sharply to unusually cold nighttime lows (near 0 degrees F) with only a small recovery during the day. We endured this unseasonable cold snap for nearly four days before it moderated. (A few days later, the outside daytime high was over 50 degrees F – you gotta love winter weather in the Northeast!)

So, what’s driving the increased – and sustained - temperatures captured by the sensor located at the top of bottom box (i.e. right in the mid-point of the two-box stack)? One possible explanation is that the extreme freeze caused the bees to shift the cluster upward in response to the cold coming in at the bottom entrance. Bees also respond to decreasing ambient (outside) temperatures by increasing the central temperature of the cluster. (Makes sense when you think about it – you turn your furnace up during cold spells, too.) While the bees aren’t “heating the hive”, they are heating the cluster, and a warmer-than-usual central temperature helps keep the bees on the outside layers from getting too close to the chill-coma range (40° F) which would be fatal to them.

Or alternatively, the increase in temperature could be an indicator that they have already resumed raising brood somewhere within the cluster, and the sensor is picking up on that. Only time will reveal if that’s the case.

Or maybe it’s just inscrutable data-noise. Time will reveal that, too.

You can keep an eye on the daily data from this hive here, and make your own hypotheses.

Even if you’re not a data-geek, the practical take-away from this is that bees scarcely use any honey at all at the start of the winter, so unless the hive was almost completely without stores, it’s unlikely it would die of starvation early in the winter. It will be very interesting to watch the hive weights throughout the rest of the winter.