To be the best beekeeper you can be, you must have a good grasp on mite biology. Failure to control mites throughout the year can easily spell doom for your bees. By understanding your enemy, you can do a better job keeping your mite levels low and your bees healthy. Varroa mites are originally a pest of Apis cerana, a honey bee from Asia. In its original host species mites only reproduce in drone cells. When varroa jumped between bee species, it rapidly evolved a number of traits that made it a more harmful pest, including the ability to reproduce in worker brood. However, mites still show a preference for drone brood, where they can produce more offspring per reproductive cycle.

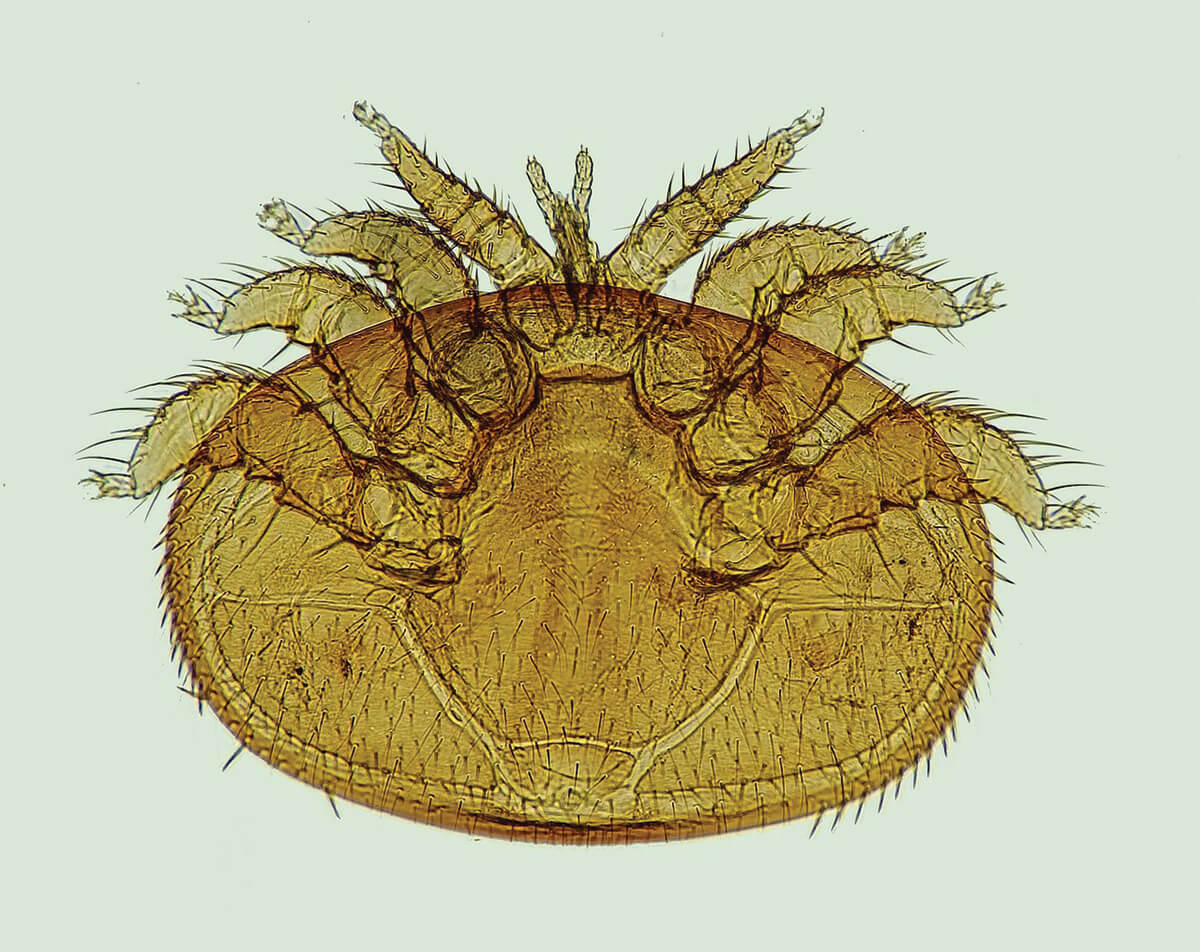

Varroa mites are arachnids

Like ticks, spiders, and scorpions, varroa mites are arachnids. This means that mites aren’t treated with insecticides but rather with acaricides or miticides that don’t target insects like your bees. Different miticides kill mites using different chemical mechanisms, and may target mites at different stages of their lives.

Mites you see are all female

The little red varroa mites in your hives are all females. They ride on bees (usually young workers taking care of brood) and feed on the nutrients in the bees’ bodies. These are called the “phoretic” mites, to distinguish them from the “reproductive” mites that are actively producing new offspring in brood cells. At different times of year, a different proportion of the mites will be phoretic vs. actively reproducing.

How mites reproduce

To reproduce, a female mite crawls into a brood cell that’s about to be capped. Once the wax cap is made, the mite begins feeding on the young bee and laying eggs. The first egg grows into a male, the subsequent eggs grow into females, and the young mites all incestuously mate with each other as the helpless bee continues its development. As the weakened bee crawls out of the cell, the mother mites and her now-pregnant daughters will emerge with her. The tiny and fragile male mite is left behind to die in the cell.

Mites feed on fat bodies

For many years, the standard understanding about varroa mites was that they feed on honey bees' hemolymph, much like how ticks or fleas feed on mammalian blood. That understanding has changed due to the work of Dr. Sammy Ramsey. Ramsey demonstrated that the mites were feeding on a bee organ called the fat bodies. That changes everything when it comes to understanding the role varroa play in winter colony survival. Varroa mites devastate honey bees by spreading lethal viruses, and we now understand that they are, almost literally, sucking the life out of winter bees as well.

The importance of mite monitoring

Monitoring for mites is an important tool for keeping your bees healthy. Regular monitoring doesn’t prevent mite problems, but it does give you the ability to avoid panic treatments, plan your treatments in advance, and even skip a planned treatment when mite levels are uncharacteristically low.

The "indirect" sticky board monitoring method counts the number of mites that fall or are groomed off the bees over a period of time. This method is the least intrusive – it doesn’t even require opening the hive to perform the test.

Direct sample monitoring using a sugar roll or alcohol wash measures the number of mites collected from a 1/2 cup (300-bee) sample. It is a more precise assessment of mite levels than using a sticky board.

Treatment Thresholds Based on Recommendations from Honey Bee Health Coalition:

| Colony Phase |

Action Not Needed Yet |

Treatment Needed |

| Dormant |

<1% |

>1% |

| Increasing Population |

<2% |

>2-3% |

| Peak Population |

<2% |

>3% |

| Population Decreasing |

<2% |

>2-3% |

% = #mites/100 bees found using an alcohol wash or sugar shake sample

Why you should make a mite monitoring plan

Varroa mite management is a year-round process, and even when you aren't treating for mites you should still be thinking about them. If you don't make a varroa management plan now, you will perpetually find yourself one step behind the mites (or two steps, or three steps…). And if you don’t kill your mites, your mites will kill your bees.

Your plan can take many forms, and the different components don’t have to be set in stone, but before this season starts you should be able to answer each of the following questions:

- How will I test my mite levels?

- How often will I test?

- What are the mite population thresholds above which I will treat my bees?

- What treatment(s) will I use? (And what other treatments will I have on-hand, in case my first choice isn’t suitable due to the local weather, or honey flow, or other factors?)

- If I had to treat right this moment, how long would it take for me to put my hands on these treatments? Minutes? Hours? Days? Weeks?

- Will I treat all of my colonies at some point, regardless of their mite levels? And if so: when and how?

How you answer those questions will depend on your location, your schedule, and your own personal preferences. However, a good mite-control plan MUST include answers to each of them, so that you're completely prepared for any and all mite-related trouble that this season may throw at you. Since your location's weather, bees, and even local mite populations may be different than someone else’s it's hard to design a perfect one-size-fits-all mite management plan.

Click the link for example plans for both the northern and southern regions in the United States: Sample Varroa Plans

Making a Varroa Management Plan Before Beekeeping Season Starts

Three Ways to Count Your Varroa Mite Problems