Entomologists and beekeepers are raising the alarm about two species of invasive hornet that could seriously impact honey bee colonies if they aren’t contained and eradicated. One hornet species was recently reported in Georgia: GDA Press Release and the other has been confirmed in past years in the state of Washington: WSDA Press Release.

What’s in a name?

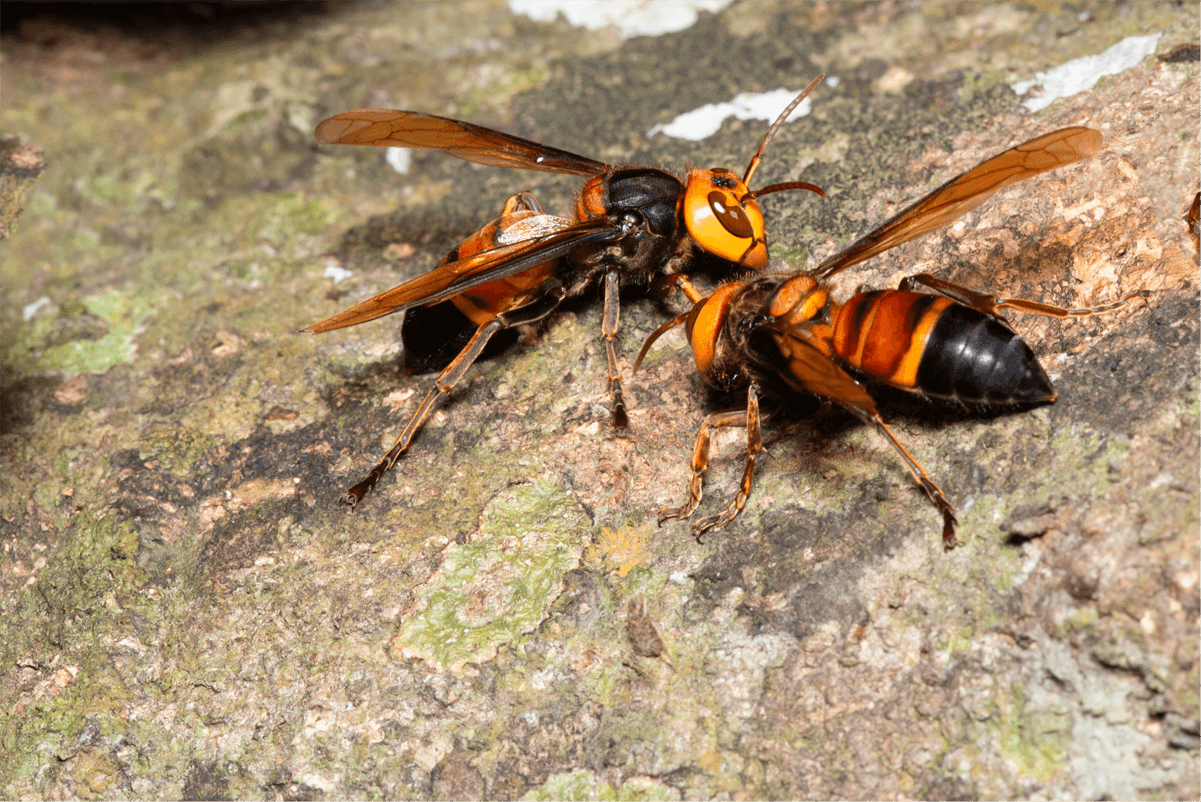

In Latin, the scientific names for the two invasive hornet species are Vespa velutina and Vespa mandarinia. The first species (V. velutina) is sometimes called the “Asian hornet”, or to be more descriptive the “yellow-legged hornet”. These are the wasps that have just been confirmed in the state of Georgia. The second species (V. mandarinia) is usually called the “Asian giant hornet”, or you may hear them called the “northern giant hornet” instead. This is the species that was identified in Washington state and Vancouver Canada in late 2019. You may have also heard the news media describe these as “murder hornets”, which is quite dramatic but not particularly accurate. There has been a push recently to change animal names to remove references to other countries or regions, out of concern that (for example) a massive government-driven push to “exterminate the Asian hornets” might accidentally provoke hostility towards Asian people, too.

Effects on honey bee colonies

In their natural range, both of these hornet species feed on honey bees, and will even specialize on bee colonies if they find a hive near their nest. They are adapted to feed on the eastern honey bee (formerly called the “Asian honey bee”) Apis cerana. This bee species has lived with these hornets for a very long time, and they have some adaptations that help them fight them off. With these adaptations, the Asian bees are able to keep things roughly in balance.

Unfortunately, our bees around here have no such defenses. When either invasive hornet species attacks the western honey bee Apis mellifera, the bees usually fail to fight them off, because they don’t have instinctual defensive behaviors that could foil the wasps. One scientific study found that “A. mellifera in France exhibit an inefficient and unorganized defence [sic] against V. velutina, unlike in other regions of Europe and other areas around the globe where honeybees have co-evolved with their natural Vespa predators.” (Arca et al. 2014: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2014.05.002)

Both hornet species will attack the guard bees and the entrance of a hive directly, even entering the hive in their assault. During these invasions, the guard bees will form balls around the hornets to immobilize them, and the bees generate heat to essentially cook the hornet to death. The Apis cerana guards produced a significantly hotter ball, and the colonies halted foraging much more substantially during wasp attacks compared to A. mellifera. (Ken et al. 2005: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-005-0026-5)

The smaller hornet species (V. velutina, the one recently found in Georgia) typically prefers a tactic called “bee-hawking” that involves a hornet hovering above the hive entrance and capturing a worker as they arrive or depart. Again, Apis cerana workers fight this by leaving their hives twice as fast as Apis mellifera workers do, which makes them much less vulnerable to a wasp attack than our bees. (Ken et al. 2007: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-006-0210-2)

How scared should you be?

Well, if you live in Washington or Georgia, there’s reason for some concern. These wasps are bad news, and you don’t want them in your apiary. Thankfully, the governments of each state are investing in monitoring and control for these wasps, but there’s no guarantee of success.

That means that even those of us further afield may someday have to deal with these wasps. However, at this point, there is no evidence that the hornets have spread further than the areas in which they have been identified, and at least in Washington, the control efforts appear to be working well. For most of us, next year’s beekeeping plans won’t have to change because of these wasps, but we can’t become complacent. There’s no guarantee that these hornets won’t be buzzing up to our apiaries at some point in the future.

Even everyday wasps can cause trouble

No matter where you keep your bees, some kind of wasp is likely to be an occasional pest of your hives. Wasps like yellowjackets or baldfaced hornets will scavenge dead bees and larvae from in front of the hive, and will sometimes invade a hive to steal live brood or honey as well. This can be especially bad later during the fall dearth, when the wasp colonies have reached their maximum population and the available food for them is very limited. A colony weakened by disease (like untreated varroa mites) can be easily overwhelmed by a strong wasp colony nearby. If you find yourself struggling with these wasps, reduce the hive entrance to help your guard bees out, and consider something more drastic like installing a Hive Gate.

Photo courtesy of the Washington State Department of Agriculture